Advances in the information infrastructure and the growing dependence of the economy and government itself on that infrastructure raise questions about its security. These questions are not new. In 1990 National Academy of Sciences, Computer Science and Telecommunications Board's (CSTB) report, Computers at Risk: Safe Computing in the Information Age, began by observing: "We are at risk. Increasingly, America depends on computers. They control power delivery, communications, aviation, and financial services. They are used to store vital information, from medical records to business plans to criminal records. Although we trust them, they are vulnerable to the effects of poor design and insufficient quality control, to accident, and perhaps most alarmingly, to deliberate attack. The modern thief can steal more with a computer than with a gun. Tomorrow's terrorist may be able to do more damage with a keyboard than with a bomb."

In 1989, another CSTB report, Growing Vulnerability of the Public Switched Network, sponsored by the National Communications System, cautioned that: "Virtually every segment of the nation depends on reliable communications .... The committee, after careful study, has concluded that a serious threat to communications infrastructure is developing. Public communications networks are becoming increasingly vulnerable to widespread damage from natural, accidental, capricious, or hostile agents."

Since those reports were written, use of networks and network-related systems has grown in the economy at large and in the government in particular. Within the government, Department of Defense (DoD) dependence on information systems and infrastructure has grown. This growing dependence is giving rise to heightened concern about the vulnerability to electronic threats of the Defense Information Infrastructure (DII) as well as the national and global information infrastructures (NII & GII) to which it is inextricably linked (notwithstanding intentionally separate components). Additional government computer and communications network vulnerability may come from the growing use of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) systems. For example, COTS constitutes over 90 percent of the information systems procured by DoD. Additionally, government procures over 95 percent of its domestic telecommunications network services from U.S. commercial carriers. These numbers are at levels that underscore the inherent linkage between defense, commercial, and civilian security concerns. Consider the following examples as additional input:

US Dependence on Information Systems

-- Internet presence as of May 1994 (internet info as quoted in the Computer Security Journal, Fall 1995)

-- One switch handles all federal funds transfers and transactions

-- with other Governmental structures and industry and private citizens through shared resources of the electrical grid, telecommunications, and the Internet

|

Trends

- transfer more than $1 trillion every day via computer

- Federal Reserve System handles more than 24,000 wire transfers per day

- Pittsburg City Paper,Vol 4, No.34, August 24-30, 1994, pp 8-9

In today's information intensive environment, the information warfare threat can come in many forms. The challenge in evaluating that threat, and the appropriate level of protection or response, has been in sorting out the actual from the perceived, and determining the potential for future developments. In order to adequately assess this threat, the Task Force divided the subject into three categories:

These threats to the National and Defense Information Infrastructures vary greatly in terms of intent, sophistication, technical means, and potential impact. The threats can be categorized into the following groups:

Based on validated incidents, some of these threats clearly exist today. Others are less certain, but can be estimated based on available technology and analysis of continuing trends in development. An estimate of the likelihood for each of these threat categories is shown below.

IW Threat Estimate

Validated |

Existence |

Likely |

Beyond |

|

| Incompetent | W |

//////////////////// | //////////////////// | //////////////////// |

| Hacker | W |

//////////////////// | //////////////////// | //////////////////// |

| Disgruntled Employee | W |

//////////////////// | //////////////////// | //////////////////// |

| Crook | W |

//////////////////// | //////////////////// | //////////////////// |

| Organized Crime | L |

W |

//////////////////// | |

| Political Dissident | W//////// |

//////////////////// | //////////////////// | |

| Terrorist Group | L |

W |

//////////////////// | |

| Foreign Espionage | L |

//////////////////// | ||

| Tactical Countermeasures | W//////// |

//////////////////// | //////////////////// | |

| Orchestrated Tactical IW | L |

W /////// |

||

| Major Strategic Disruption of U.S. | L |

W = Widespread; L = Limited

The information throughout this Appendix was compiled from unclassified sources and briefings received by the DSB from subject matter experts within the Department of Defense, and throughout the civilian sector.

IW-related incidents date back to the mid 1980s with the growth of personal computers on a worldwide scale.

IW-Related Incidents

There Really Is A Smoking Gun

|

The well known case involving the Hanover Hackers is one of the first recorded incidents and is considered to be an example of hacker activity performed for the challenge of gaining entry into someone else's system -- without malicious intent.

Although most Public Network (PN) attacks are aimed at accessing other systems, or avoiding toll charges, the software time bomb attacks indicate that denial of service was the objective.1 (Note: References are at Attachment 1to this Appendix). In the case involving Dutch teenagers, sensitive information related to U.S. war operations during Desert Storm was modified or copied. Access techniques used in this case included INTERNET and other networks.2 The Rome Labs incident is another highly publicized case which eventually revealed that over 150 INTERNET intrusions had occurred between 23 March and 16 April 1994. The intrusions were accomplished by a 16-year old British hacker and an unknown accomplice. Several research programs and systems were compromised through the use of Trojan Horses and Network Sniffers. The individual was eventually apprehended by Scotland Yard, and is awaiting prosecution.3

In the 1994 attack on Citibank, an international crime group used the electronic transfer system and the international phone network to gain access and transfer approximately $12M to their own accounts. Prosecution of individuals apprehended in Russia and several European countries is pending at this time.4 In December 1994, a group known as the INTERNET Liberation Front was charged with stealing phone net data, performing INTERNET attacks for money, and development of highly sophisticated attack tools. Numerous phone, information service, and INTERNET providers were attacked, including some government systems. There was also a substantial international component to their activity based on membership involving at least eight countries.5 The MCI incident involved an engineer who electronically collected 60,000 calling card numbers and sold them to an international crime ring. To accomplish this task, the individual penetrated several barriers which could have shut down the switch for a prolonged period.6

A final example is a case involving a programmed test of electronic systems vulnerabilities. An Air Force hacker remotely entered the command and control system of a ship at sea, through use of a standard computer, INTERNET connection, and the E-mail system onboard the ship. Access included ship navigational control systems which could have effected ship performance or response to guidance commands.7

The cases listed here are certainly not an all-inclusive list. They do support an alarming trend toward widespread vulnerability on a case by case basis. The major concern involves what the potential outcome would be if these types of attacks were coordinated to occur simultaneously, or if the tools and techniques used were applied with a more subversive intent.

In order to more clearly identify the suspected threat, the Task Force considered a variety of sources for analytical support, and paid particular attention to some of the more detailed threat and vulnerability assessments accomplished within the last year.

The Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) conducted an extensive vulnerability assessment of government network systems in 1994 and 1995. A summary of the DISA focus, and findings is shown below8:

IW Assessments - DISA Report

Focus:

Findings:

- DISA assessment verified that less than 5% of all attacks are ever detected, and of those, less than 3% are reported. |

The result of this report was an increased awareness of a growing problem, but the initial actions were primarily focused on security awareness training, and increased training for Local Area Network (LAN) managers. Indications from DISA are that numbers of reported attacks remain at single digit percentage levels, and the problem continues to grow.

At the request of Congress, the General Accounting Office (GAO) conducted an assessment, with the report published in June, 1996. A summary of the GAO focus, findings, and recommendations is shown below 9:

IW Assessments - GAO Report

Focus:

Findings:

Recommendations:

- Report all security incidents within the Department.

|

Results of this report have been forwarded to the Senate Armed Services Committee and House Committee on National Security; the Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Defense, and the House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on National Security; the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence; the Secretary of Defense; the secretaries of the military services; and the Director, Defense Information Systems Agency.

The report concludes that there are significant risks based on these findings:

According to the FBI and Defense Investigative Service (DIS), high technology and defense- related industries remain the primary targets of foreign economic intelligence collection operations. This finding continues a trend reported in the 1995 Annual Report. The most likely industry targets of economic espionage and other collection activities during the past year include the following areas, most of which are included on the 1996 Military Critical Technology List (MCTL):10

According to a DIS summary of suspicious contacts reported in FY95, entities associated with 26 foreign countries displayed an interest in 16 of 18 technology categories listed in the new MCTL. The U.S. considers all of the above industries to be strategically important because they produce classified products for the government, produce dual-use technology used in both the public and private sectors, or are responsible for the leading-edge technologies required to maintain U.S. economic security.10

FBI Director Freeh provided the following five examples of foreign targeting activities in his 28 February 1996 statement before the Senate Judiciary and Intelligence Committees:

Types of U.S. government economic information -- pre-publication or unpublished "insider" data -- of special interest to governments and intelligence services include:10

Three additional case studies were reviewed by the Task Force involving a southeast U.S. port city, a rail traffic control center, and a 1996 Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) vulnerability assessment. A summary of the findings:

- Identified single point of failure for infrastructures supporting military mobilization and deployment

- Central control switching facility for east coast rail traffic.

- Not vulnerable today due to antiquated systems, limited networking, and proprietary software.

|

Details of the assessment which could impact deployment of units and follow-on forces which rely on transport out of the port terminal region are provided in Reference 13. Investigation of the AMTRAK - MARC collision indicated human error, but vulnerabilities were detected in the control center, making it a potential single point of failure for exploitation. The FAA assessment, provided in briefing form to the Task Force in June, 1996, concluded that even though vulnerabilities were likely to grow, financial realities restricted the ability to plan protective measures into proposed upgrades until mandated, or in worst case, following a major incident.11

The trends seen in development of intrusive tools on the INTERNET, growth in hacker activity, and related incidents cause further concern. A summary of recent trends is given below:

IW Trends

- SATAN made available to the public, April 1995.

- Masters of Deception: Programmed attacks on phone companies.

- Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences Study indicates that 98.5% of participating businesses had been victims of computer theft or attempted theft.

|

Tools: The NSTAC Assessment of Risk to Security of Public Networks reported in February, 1996 that SATAN, the Security Administrator Tool for Analyzing Networks, scans and reports system vulnerabilities, which if improperly used, could enable system attacks. It was made openly available on the INTERNET in April, 1995. The report also identifies Rootkit as a tool which falsifies data, making detection of intrusion difficult even with state-of-the-art technology. Rootkit is also openly available on the Internet

Hacker growth: Additional case study information is provided at Attachment 1 for first three listings. In the case of the 5-hacker group, one raid wiped out data on the Learning Link, a NYC public television station computer serving hundreds of schools.2 The Moon Angel offenses included breaking into NASA computers controlling the Hubble telescope, and rerouting calls from the White House.

In October, 1995 New York officials made arrests in what was declared the largest cell phone cloning operation in the country. Estimates are that over 27,000 phones were cloned within a seven month period at an estimated loss of $1.5M per day in cell phone revenue nationwide.2

Finally, consider the World Trade Center bombing as a case which might be a good example of physical versus virtual attack: Twin tower, 110 story building; 50,000 workers and 80,000 visitors daily vs. Global marketplace nerve center, many City/State/Federal offices, several international office, $3M phone switch station, telecom for Wall Street to the World.12

These trends are cause for a growing concern -- the unknown threat, and the potential for an attack having strategic significance.

Existing, easily acquired capabilities make the potential for an attack having strategic significance a reality. The most common capabilities for IW-related attacks are, by themselves, often seen as more of a localized nuisance, rather than a strategic threat. When applied in a coordinated attack however, the results are far more widespread. Consider the Nth order effects in the following example from Col Charles Dunlap's essay, "How We Lost the High-Tech War of 2007", published in The Weekly Standard, January 29, 1996:

The Setting: (The year 2007):

- Downsizing and cuts in military infrastructure are "off-set" by information technology.

- COTS technology used widely by U.S. and her adversaries.

- Open architecture provides information equality - not information dominance.

- U.S. insistence on open architecture leaves sources of information readily available to opponents - News media is a particularly valuable source.

- Warfare has become even more savage - not cleaner, more high-tech. Televised atrocities and deaths of U.S. troops become a tool of adversaries to sway public opinion.

The Indirect Attack - U.S. C2-Protect efforts are successful in countering direct attack - leading adversary to indirect attack with many Nth order effects:

Mexican economy attacked - computers corrupted on a massive scale

Counterfeit electronic pesos flood Mexican bank accounts

Hyperinflation; economy collapses

Refugees flood into U.S.

Call for troops to be brought home to face domestic situation.

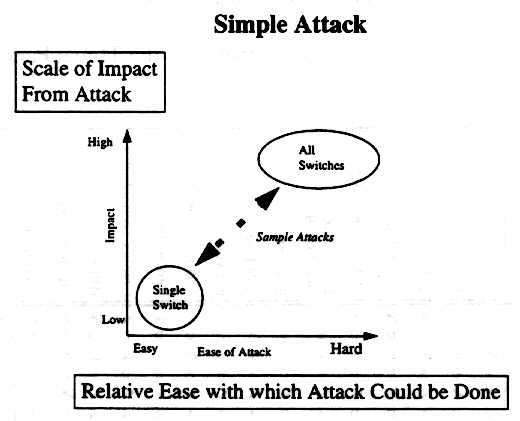

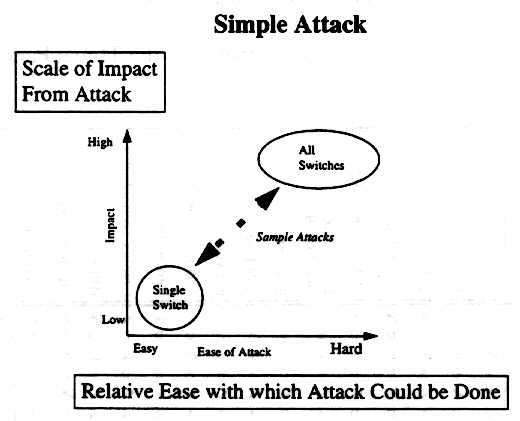

The technologies required to perform this these types of attack are available today. The issue of whether or nor they comprise a strategic threat is more a matter coordinated timing. Some may come in the form of a simple attack on a target identified as a single point of failure:

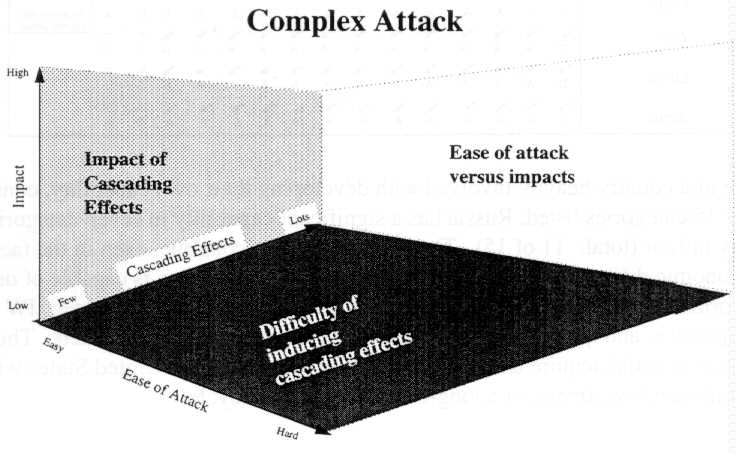

A more complex, coordinated attack takes on a multi-dimensional nature:

In either of these cases, the timing of the attack is what in fact may have

made it strategic in nature. Consider the port city

example:13

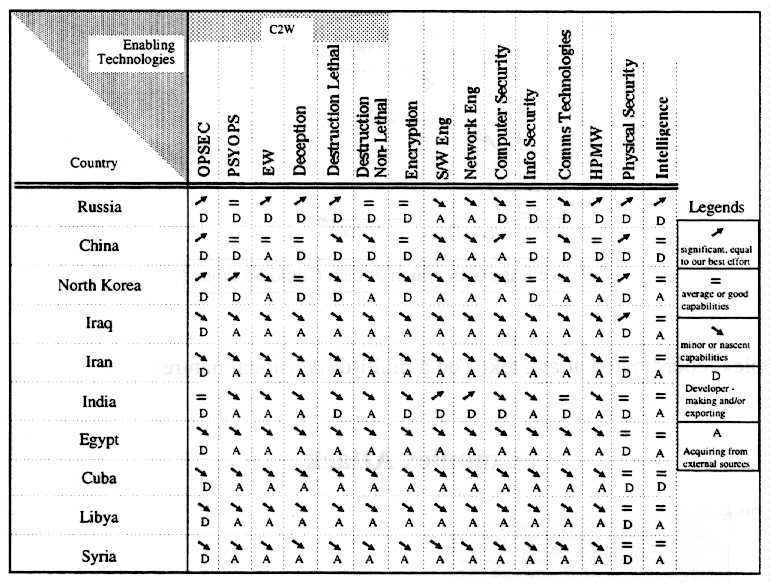

To demonstrate the relative ease of achieving an IW capability, the Threat Panel prepared the following table:

As an example of a country heavily involved with developing their own capability, consider Russia. Of the 15 categories listed, Russia has a significant capability in seven categories. and a good capability in four (total: 11 of 15). These developments continue, even in the face of widespread economic difficulties. More importantly, almost any nation is capable of developing significant Information Warfare capabilities. Unlike nuclear capabilities, however, IW is relatively inexpensive, and quick to obtain, given the volume of available markets. Thus, a country such as Iran could acquire a strategic capability to threaten the United States without requiring a significant investment, or a long-term development cycle.

In order to best understand the significance of a potential IW threat, we must consider the often opposing views of information security between the private/commercial sector, and the national security view:

Merging Two Views On Information Security Into One

National Security View:

Private Sector / Commercial View:

National and Private Sector Information Security Are Now Inexorably

Intertwined:

Strategic Sanctuary Is At Risk

|

The private sector has viewed IW as a cost of doing business that was often

passed on to the customer. The national focus still struggles with the concept

of what constitutes a strategic threat. The response has been to avoid risk

rather than manage and anticipate it. A zone of cooperation is now emerging

which must be better defined:

These issues are at the heart of the defensive information warfare issues.

1. NSTAC Assessment of Risk to Security of Public Networks, Feb 1996.

2. Trends and Experiences in Computer-Related Crime, Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences, 1996.

3. Rome Lab Attacks Final Report, 20 Jan 1995.

4. Senate hearing on Security in Cyberspace, 5 June 1996.

5. Trends and Experiences in Computer-Related Crime, Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences, 1996.

6. 1995 DSB Report.

7. "Hacker Exposes U.S. Vulnerability," Defense News, Oct 9-15, 1995.

8. DIS Briefing, "Developing the Information Warfare Defense: A DISA Perspective," given by Mr. Bob Ayers, March 1996.

9. GAO Report, Information Security: Computer Attacks at Department of Defense Pose Increasing Risks, 22 June 1996.

10. 1996 CSI/FBI Computer Crime and Security Survey, as reported in Computer Security Issues and Trends, Volume II, Number 2, Spring 1996.

11. FAA Briefing, "Security of the Air Traffic Control System," given by FAA representatives, Mr. Dennis Hupp and Ms. Trish Hammer, June 1996.

12. NSA Briefing, "Ensuring Information Superiority for the 21st Century," Driven by LtGen Minihan, May 1996.

13. Joint Program Office (JPO) Briefing, "Infrastructure Assurance Supporting Military Operations," given by the Joint Program Office for Special Technology Countermeasures, Ms. Susan Hudson and Mr. Bob Podlesney, July 1996.