IW-D

The Task Force agrees with the observation of the Deputy Secretary shown in Exhibit 3-1 below. This section discusses several areas in the Department and in the larger national security environment where we can make rapid progress on responding to this challenge.

|

Exhibit 3-1. Initial Observations

The threat posed by information warfare is not limited to the realm of national defense, and the effort to control the problem must encompass broader national security interests, including Congress, the civil agencies, regulatory bodies, law enforcement, the Intelligence Community, and the private sector.

Unlike an attacker in conventional war, an attacker using the tools of information warfare can strike at critical civil functions and processes such as telecommunications, electric power, banking, or transportation and other centers of gravity or even at the stability of the social structure, without first engaging the military. Such a strategic information warfare attack can occur without forewarning or escalation of other events. In addition, attacks on the civil infrastructure could impede the actions of the military as much as a direct attack on the military's force generation processes or command and control.

However, we should not forget that information warfare is a form of warfare, not a crime or act of terror. The Secretary of Defense individually and the Department of Defense collectively, have two basic responsibilities -- to provide for the "common defense" of the United States, and to be "ready to fight ... with effective representation abroad" [A National Security Strategy of Engagement and Enlargement, The White House, February 1996]. By first focusing on improving its ability to manage the information warfare challenge to the defense mission, the Department can meet its national defense responsibilities while also enhancing its ability to play a significant role in defending against and countering a strategic information warfare attack on national centers of gravity.

Keep in mind that information warfare is not limited to attacks on computers: The potential targets of information warfare attacks can include information, information systems, people, and facilities that support critical information-dependent functions. The means of attack can be both cyber and physical. Finally, information warfare is adaptive and the practitioners learn from their experiences. While this phenomenon is not unique to information warfare, the speed at which the learning process takes place has no parallel in other forms of warfare.

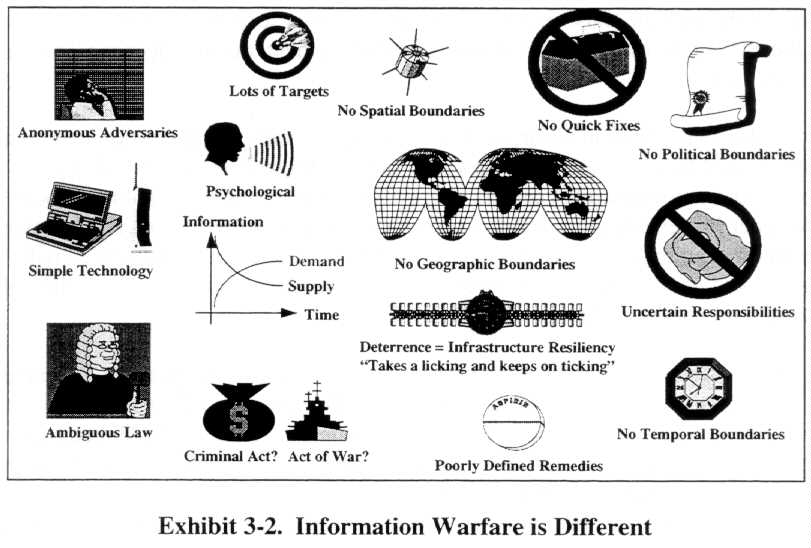

Exhibit 3-2 suggests some additional ways in which information warfare is different from conventional warfare. Information warfare offers a veil of anonymity to potential attackers. Attackers can hide in the mesh of inter-networked systems and often use previously conquered systems to launch their attacks. The lack of geographical, spatial, and political boundaries in cyberspace offers further anonymity. Information warfare is also relatively cheap to wage as compared to conventional warfare, offering a high return on investment for resource-poor adversaries. The technology required to mount attacks is relatively simple and ubiquitous. During an information warfare engagement, the demand for information will dramatically increase while the capacity of the information infrastructure to provide information may decrease. The law, particularly international law, is currently ambiguous regarding the definition of criminality in and acts of war on information infrastructures. This ambiguity, coupled with a lack of clear designated responsibilities for defense, hinders the development of remedies and limits response options. Finally, deterrence in the information age is measured more in the resiliency of the infrastructure than in a retaliatory capability.

Exhibit 3-3 shows that information warfare has been particularly troublesome for the Intelligence Community because IW is a non-traditional intelligence problem. It is not easily discernible by traditional intelligence methods. Formerly, capabilities were derived from unique observables and indicators of military capability open to our sensors, amenable to cataloging in databases, and understandable by classic analytic techniques. With information warfare, however, the following elements come into play:

- What do we need to know? What should we look for? Where do we look?

- Observables, indicators, experience, databases, analysis techniques, ...

- Computer scientists, network engineers, electronics engineers, business process engineers |

Exhibit 3-3. Intelligence Community Observations

- The physical attributes of conventional and nuclear forces can be observed and quantified. The alert posture and movement of forces provided indications of potential threat. Our understanding of such patterns gained from long experience in observing known adversaries, the orders of battle stored in our databases, and the related analytic skills were well suited for understanding historic threats and from such insights we derived "intent." These skills are largely irrelevant in the information warfare environment.

- Now, key technologies designed for completely innocent applications can be used as weapons. For example, software used to test systems can also be used to penetrate systems.

- The technology required for information warfare is available everywhere.

- However, the "business" or "war" processes that must be penetrated to determine capabilities and intent are relatively complex, which means that human intelligence and counter-intelligence will continue to play a vital role. It is not easy to identify sources of attacks, intent, etc. in the information age.

- Finally, the technical skills required by our intelligence collectors and analysts in order to deal with these new challenges are much broader and deeper and more sophisticated than those required in the past. The intelligence community will require more personnel with advanced scientific degrees and a deep technical understanding of process, computer, and network design and of leading-edge technologies to meet the challenge adequately.

The Task Force derived a taxonomy of information warfare that describes information warfare. Unfortunately, as shown in Exhibit 3-4, in those cases where both objects and processes are present, this taxonomy would not scale in a linear manner beyond three levels. This is the result of the number of permutations and combinations by which the attacks could be mounted against a particular process, over variable time periods. The derivation of the taxonomy is discussed in Appendix C, A Taxonomy for Information Warfare?

However, by adopting concepts from Joint Pub sources and inputs of the Threat and Policy Panels of the Task Force, we developed a standard vocabulary for use in threat alerting and for the assessment and reporting of defensive preparedness, tied to specific information dependent processes. This vocabulary is discussed in Section 6, Recommendations.

- Task Force could not find or derive a useful IW taxonomy

- Focus too broadly (GII/NII versus DII) or narrowly (definitions, legal)

- Current practices trade off security |

Exhibit 3-4. Additional Observations

Resources have been focused historically on protecting classified content and systems. These classified systems constitute only a very small percentage of the challenge.

Sometimes, we just make the problem too hard by failing to focus on what can and should be done. We can focus too broadly, too narrowly, or on the wrong problem set.

The reality of limited resources has fostered the current acquisition practice of trading off functionality, performance, and numbers of systems delivered to the operating forces at the expense of security. On a positive note, recent policy updates clearly state the need for attention to the information warfare aspects of systems acquisition. For example, DODD 5000.1 indicates that acquisition programs should consider how systems security procedures and practices will be implemented and how the system will be able to respond to effects of information warfare. The Directive also calls for a C41 Support Plan for each system. The Task Force was disappointed to note, however, that the Support Plan does not include information warfare considerations. DODD 5001.2-R also specifies that the operational requirements documents must include the characteristics the system must have to defend against and survive an information warfare attack.

Bottom line -- policy exists, it is not yet uniformly implemented or enforced, and it requires resources in implementation.

Exhibit 3-5 suggests that infrastructure resilience has been demonstrated repeatedly during natural disasters, but overall robustness against a major IW attack is untested. Thus, national infrastructure recovery must be considered uncertain. Given the complexity and interconnected nature of our infrastructures, we really do not know the extent of our vulnerability. The possibility of cascading effects occurring throughout and between infrastructures certainly exists. This was adequately demonstrated in the 1991 regional long-distance telephone failures (attributed to a simple programming error), the recent West Coast power failures, and the 1988 Morris worm propagation throughout the Internet (damage was limited to UNIX systems demonstrating the value of system diversity). The Morris worm example is noteworthy in that warnings of the worm were often sent over the Internet because emergency response personnel did not have the telephone numbers of colleagues in other organizations to whom the warnings needed to be sent. In many cases, these electronic warnings carried the worm with them and aided the propagation of the worm.

|

Exhibit 3-5. Additional Observations

The concept of protecting large portions of the information infrastructure is not valid. It is economically and technically impossible to close every possible vulnerability. We need to focus on designing a resilient and repairable information infrastructure. Our experience in designing highly reliable computer systems does not scale to a large, distributed information infrastructure. Our design practices are not based on the possibility of malicious events. We need to focus on establishing information domains within the information infrastructure, which will minimize cascading effects and which will enable us to contain the battle damage which might result from an information warfare attack. And, since we cannot yet effectively employ area and perimeter defenses, we do not really know what the implications of scale are in establishing an effective information warfare (defense) capability.

The Task Force does not want to imply that the various actions taken over the years by the information security or INFOSEC community do not have roles in IW defense. INFOSEC is an important contributor to achieving a robust information warfare defense capacity. Unfortunately, to many, INFOSEC has become shorthand for protecting the confidentiality of information.

Although important, the steps needed to ensure confidentiality are not adequate to achieving information assurance in an information warfare environment.

Encryption may be an example of trying to make the problem too hard, as shown in Exhibit 3-6. The nation has focused a lot of attention and energy on the encryption policy debate. Encryption simply does not solve all of the information security problems. The Task Force believes the policy debate has been a distraction from efforts to enhance the resiliency of the critical national information services.

Encryption is useful... - But

- And the NRC report provides useful insights

|

Exhibit 3-6. Additional Observations

The Task Force reviewed the NRC report and was briefed on the study effort. While the Task Force felt that the report provided some useful insights, namely that the non-confidentiality applications of encryption provide significant benefit for user authentication and data integrity, the Task Force also believes that access control and identification and authentication are more efficient than encryption in "raising the bar." It also suggests that escrowed encryption be explored and that attempts be made to promote information security in the private sector. On the basis of the review and briefing, the Task Force determined that a further detailed examination of the encryption issue would probably not yield any additional major insights.

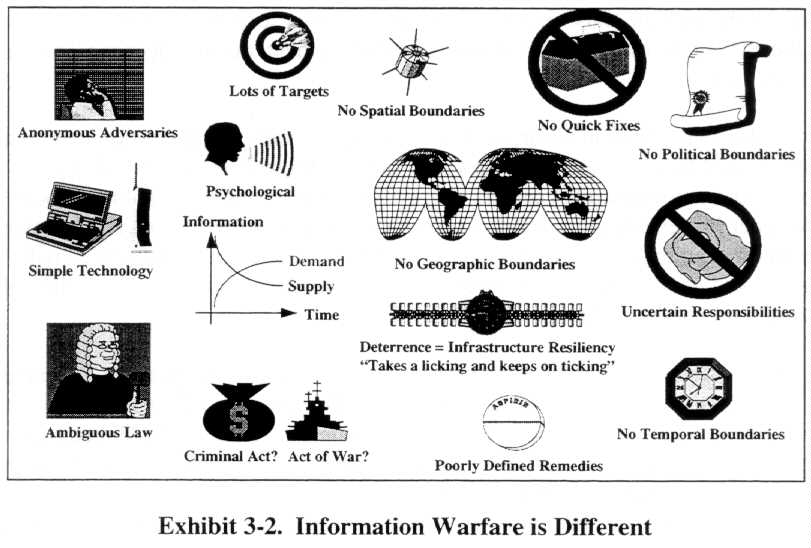

The Computer Security Act of 1987, the recent Clipper debate, and the continuing encryption policy debate highlight the private sector and civil agency reservations about the role of DoD in the area of national information protection. Exhibit 3-7 shows this role.

Market forces are extremely powerful, but will not alone provide the capability desired. The market simply does not perceive the possibility of a strategic information warfare attack against information centers of gravity. The market is not sufficiently informed about the vulnerabilities and threat to make rational national security judgments. Further, there may be little economic motivation to invest in security or even strong market incentives to resist adding security. Where there is commercial awareness, it is focused on protecting against theft of data and services (e.g., credit card numbers, telephone service) and alteration of data (e.g., financial accounts). Denial of service attacks are not an area of major concern for commercial entities. Managing the problem will require some legislation, some additional regulation, some indemnification of the private sector to achieve desired assurance goals, and some incentives (such as revisions to the tax structure).

The seams are critical. Currently, information necessary for an effective information warfare (defense) capability is not shared effectively across the seams. Information warfare (offense) is highly compartmented in spite of the fact that it shares common technology and operating environment with the information warfare (defense) community. In some cases, the military, law enforcement and intelligence communities are restricted by law, executive order, or regulation from sharing certain information. Historically, these communities are notoriously bad at sharing information. There are very few mechanisms for government and industry to share sensitive information such as vulnerabilities and intrusions. This lack derives primarily from the competitive sensitivity of information that is required for an effective information warfare (defense) capability.

In addition, at the national level, there are competing equities at stake in nearly every information warfare issue. Not only do these interests compete among each other, there are competitive forces within each of the sectors. Some examples are shown for each of the four equities. Resolution of the information warfare (defense) issues at the national level will be a time- consuming and laborious process. While it may not be possible to balance the equities, the key is to provide a mechanism to discuss rationally and deal with the legitimate equities of the participants. Grappling with this problem on the national level will require a very broad perspective if we are to ensure that national, regional, and local interests are served.

While information warfare (defense) is an extremely complex problem set, there is a lot that can be done with a limited number of resources quickly. Many of the Task Force recommendations identify these possibilities, some of which are shown in Exhibit 3-8.

- Awareness, training and education and clarity of organizational responsibility and accountability are seen as yielding the largest short- term improvements

- Can't wait for the Presidential Commission to report out |

Exhibit 3-8. Additional Observations

Finally, DoD must start now to implement the recommendations of the Task Force. This is the third year in a row that a task force of the Defense Science Board has issued a call for action. The President's Commission will be occupied with issues that transcend the Federal government and the private sector. DoD cannot afford to wait for all of these higher level issues to be resolved before embarking on a concerted effort to grapple with those issues that are within the authority of the Secretary of Defense to address.

[End Section 3.0]