November 24, 2000

THE FIFTH BOMB:

DID PUTIN’S SECRET POLICE

BOMB MOSCOW IN A

DEADLY BLACK OPERATION?

John Sweeney on the evidence that the old KGB

deliberately planted bombs in Moscow and

blamed them on Chechen terrorists.

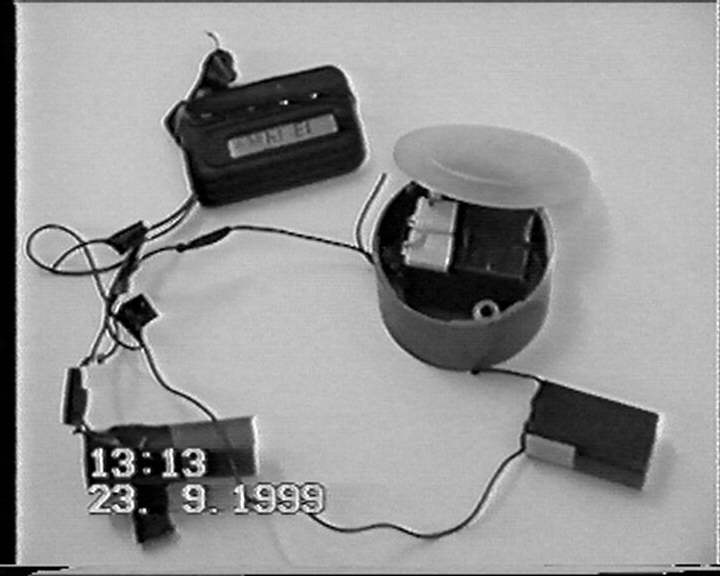

The critical evidence are these photographs of a detonator.

The photographs of a detonator, taken by a Russian bomb squad, and other fresh evidence point to a plot carried out by the FSB working to assist their old spymaster, Vladimir Putin, in his rise to control the world’s number two superpower and its nuclear arsenal.

The secret policeman stood on the

edge of a field of rubble and burnt wreckage, the ruins of what had been

only the night before a block of flats.

He looked Central Casting’s idea of a KGB operative, sporting a cowpat hairdo, a cheap black raincoat, black tie, lean, tall, clean shaven, saturnine. They call the KGB the FSB these days, a new name for the Soviet state’s old organ of terror.

There had been two bombs in Moscow in four days. The first bomb exploded just after midnight at a block of flats at Guryanov Street. It killed 92 Muscovites sleeping in their beds in the early morning of 9th September, 1999. Several bodies were rocketed into the surrounding streets. By daybreak people could see the sad detritus of the atrocity: children’s clothes, a sofa hanging off a ledge in what had been someone’s living room, open to the sky, books, pictures scattered far and wide. Broken glass crackled underfoot in all the surrounding streets. The edge of fear in Moscow was tangible.

Four days later the second bomb blew up a similar block of flats at Kashirskoye Highway at five in the morning. The wounded, shocked, painted in dust, as semi-naked as when they went to sleep, a night and a lifetime ago, were carried off in stretchers. The most haunting image was of a man quite blackened by soot from a fire, crawling on his hands and knees through the wreckage: more beast than man. He survived. 130 other residents in the block of flats - men, women, children - did not.

Enter the secret policeman. He walked up to the TV cameras and presented to the compound eye of lenses a black and white e-fit picture. The e-fit depicted a Chechen man, with a fleshy face, almost Buddha-like in its plumpness, swarthy skin and tinted spectacles. This was the Chechen terrorist the authorities were blaming for the bomb. He was using the name of Mukhit Laipanov, who had recently rented ground floor space in the two apartment blocks devastated by the bombs. The real Laipanov died in a car crash earlier in 1999. The authorities were very quick to pin the blame on a group of Chechen trained terrorists. It was the Chechens who did it - that was the instant effect of the secret policeman’s e-fit. It was posted up all around the bus stops of Moscow. The Russian authorities have yet to produce a single solid piece of evidence to support their theory that Chechen terrorists blew up Moscow. No-one has been tried, no chain of evidence explained. A few men have been arrested, but none of the alleged ‘ring-leaders’. Three days after the second bomb, the bulldozers moved in, obliterating the sites and also destroying evidence against the bombers.

Two more bombs had exploded in cities in southern Russia. The four bombs together killed more than 300 people in less than two weeks.

There was a fifth bomb. This one didn’t go off. But the fifth bomb - proved by photographs of its detonator shown above - provides hard evidence that challenges the official ‘Chechen version’ of the Moscow bomb outrages. The fifth bomb points the other way: that the KGB-FSB bombed Moscow deliberately to blacken the name of the Chechens as a pretext for the second Chechen war.

The photographs of a detonator, taken by a Russian bomb squad, and other fresh evidence point to a plot carried out by the FSB working to assist their old spymaster, Vladimir Putin, in his rise to control the world’s number two superpower and its nuclear arsenal.

When the two Moscow bombs went off, Putin had just been appointed prime minister by President Yeltsin. With no public track record, the former secret policeman was widely mocked as a political nobody, a cold, faceless Kremlin insider who had spent 16 years in the KGB and had emerged as the chief of its successor, the FSB. Boris Kagarlitsky is a seasoned Kremlin watcher in Moscow: ‘You cannot turn a bureaucrat into a glamorous person. He is as grey as he used to be. There is a propaganda machine which works but that is exactly the weakness of Putin, because as a politician he is a nobody. To be a politician you need some kind of past.’

Matt Ivens, editor of the Moscow Times, thought the same: ‘Yeltsin had been through a couple of prime ministers and each time he dropped them he made it clear that it had something to do with elections.

By the end he's picking Vladimir Putin. No one has ever heard of Putin, except very careful watchers of politics or people from St. Petersberg. He's announcing "this is my successor, this is a man who can run the country" and there is widespread ridicule. All the newspapers in town including ours said, there's no way this guy could win an election, unless something really extraordinary is going to happen.’

The Moscow bombs were the extraordinary thing.

Putin struck out in the immediate aftermath of the bombs: ‘Those that have done this don't deserve to be called animals. They are worse … they are mad beasts and they should be treated as such.’

His poll ratings soared, and he struck again: ‘we will waste them. Even when they are on the bog.’ This was pure gangsterese, but it went down a treat with the Russian public. Putin was working with the grain of Russian racism. For centuries, the Muslim renegades from the savage rocks of the Caucases have been the folk devils of Russia. The nineteenth century poet Lermontov wrote a lullaby which has stuck in the Russian mind:

‘The Terek streams over boulders,

the murky waves splash;a wicked Chechen crawls on to the bank

and sharpens his kinzhal;But your father is an old warrior

forged in battle;sleep my darling, be calm,

sing lullaby.’

The Chechens had humiliated the might of Russia in the first Chechen War, which Yeltsin had started in a drunken rage in 1994. They had kidnapped and killed mnay Russian soldiers, sometimes in a bloody and disgusting fashion.

The Islamic terror

Now it was the turn of the old guard, the Russian military and the FSB, to get their own back. And the Chechens were wasted, Grozny mulched to rubble, again, their economy annihilated, their ecology destroyed, their men shot and tortured and dumped in pits - to this day.

The tanks started to roll, and the war in Chechnya which has seen a Russian victory at the expense of thousands of civilian lives, began.

Putin’s brisk, savage reaction to the Moscow bombs made him a Russian superstar. The Chechens lost everything they had gained from the first war. One Chechen view is this: ‘if we had wanted to bomb Moscow, we would have blown up the Kremlin or a nuclear power station. Why should we blow up a couple of blocks of flats?’ Putin’s tough guy stance saw his opinion poll ratings rocket from close to zero to 70 per cent. Hugely popular, he was anointed President of the Russian Federation by Boris Yeltsin on New’s Year Eve. Sick, drunk, a joke but not a funny one, Yeltsin bowed out, escaping a fraud and money-laundering investigation by the Swiss Chief Prosecutor which was getting very close to his ‘family’ in the Kremlin.

Earlier in 1999 Special Prosecutor Yuri Skuratov had been hot on Yeltsin's case. He had received damning evidence from the Swiss investigators, evidence that put Yeltsin’s daughter, Tatiana, directly in the frame. Then he got a phone call. ‘We’ve got you on tape. Resign, or you’re finished.’

Skuratov refused to be blackmailed – and then Russia's TV millions saw him being entertained by two young prostitutes. They saw their Special Prosecutor lying on his back, naked, one of the woman on top of him, her head bobbing up and down. It was a classic dirty trick.

And the man responsible? Skuratov said: ‘As head of the FSB, Putin was one of those who fought against me, who compromised me, who plotted to get me off the case.’

The shaming of Skuratov finished off the Special Prosecutor, but not the case. By August 1999, the evidence against Yeltsin and his family was growing. It centred around an expensive refurbishment of the Kremlin, the central allegation being that a Swiss businessman of Albanian origin had supplied credit cards to members of Yeltsin’s circle in return for the contract. Worse, the evidence was in Swiss, not Russian, hands. Yeltsin’s popularity rating was hitting 2 per cent. At that point he promoted his spy chief, Putin, and made him prime minister.

At the same time Russian TV showing a video of clip of Chechen guerrillas purportedly torturing and killing Russian soldiers. The worst clip shows a knife being put to the neck of a shaven-headed white man. Then his artery is severed and one can see his blood drain from his face in close-up. The next shot is of the man lying prone on the ground, to all intents and purposes a corpse. There is no way of telling whether the victim was a Russian soldier and the killers Chechen, no supporting evidence. Nevertheless, this and other clips were shown on Russian TV repeatedly - as if someone in authority was minded to soften Russian public opinion against the Chechens. And this happened before the bomb outrages.

The first came in the southern city of Buinaksk, killing 62 in September 4th, 1999. Then came the two bombs in Moscow, then a fourth that killed 17 in the southern city of Volgodonsk on September 16th.

The Russian government’s case that Chechen terrorists or Chechen-backed terrorists bombed Moscow and the two towns in southern Russia was spelt out by Vladimir Kozlov, head of the FSB’s anti-terrorism department, in a Moscow press conference a year after the outrages. Kozlov said that the terrorists were members of a radical Islamic sect, led by one Achemez Gochiyayev, who was paid $500,000 by the feared Chechen warlord Khattab. He recruited Yusuf Krymshamkhalov and Denis Saitakov to deliver the Moscow blasts. None of these men have been arrested. But two other men have been: Taukan Frantsuzov and Ruslan Magayayev. The evidence against them, when or if it comes before the courts, is keenly awaited.

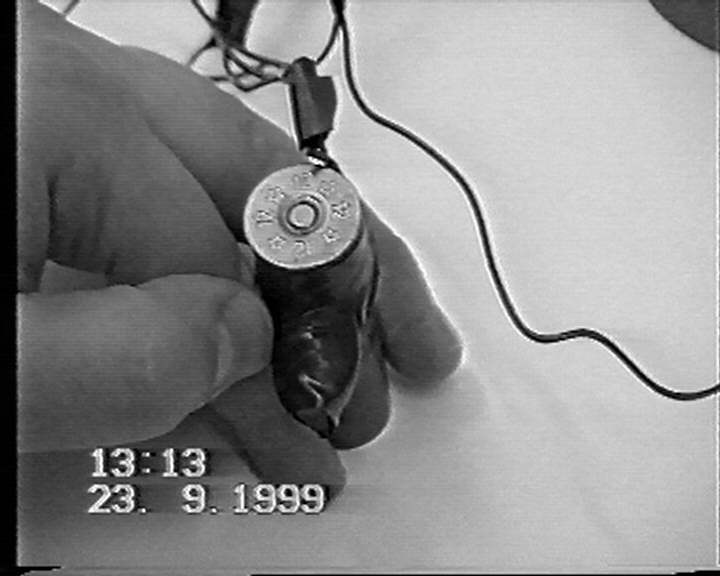

The terrorists were trained in Chechnya, then dispatched to neighbouring North Caucasian republics, such as Karachayevo-Cherkassia, with tons of explosives, said the FSB. There, they rented trucks and smuggled the explosives to Moscow, usually camouflaged as sugar, potatoes or some other produce. Most of the bombs were made of a mixture of potassium nitrate and aluminium powder, with Casio watches used as timers, according to Kozlov. FSB detectives say they also found 500 kilograms of this mixture near the Chechen city of Urus-Martan in December, 1999, citing this as proof that those responsible for the attacks were not only trained in Khattab’s camps in Chechnya, but also obtained explosives there.

Common sense says it would be madness for a group of Chechens to smuggle explosives all the way from Urus-Martan to Moscow. Since the first Chechen war, Chechens are routinely singled out for harrassment by Russian police, vehicles stopped and searched, identity papers demanded. Besides, there has long been a strong Chechen mafia in Moscow, very capable of getting its own hands on arms or explosives locally. In Russia, you can bribe your way into a nuclear rocket silo or buy the list of the lost sailors of the doomed submarine, the Kursk. The ‘Chechen terrorists’ would have been risking a great deal by hauling their explosives roughly 1,000 miles to Moscow, when they could have bought them locally.

Six of the suspects, including those for the bombs in southern Russia, have been killed in fighting with federal forces in southern Russia. Dead men don’t tell tales. Much of the evidence presented at the FSB news conference was circumstantial.

But the FSB’s official version of the bomb outrages starts to fall apart when you examine the case of the fifth bomb. The story of its discovery, defusal and denial casts huge doubts on the Kremlin’s line.

Around 9pm at night on 22 September in the provincial city of Ryazan, 100 miles south east of Moscow, Vladimir Vasiliev, an engineer coming home for the night noticed three strangers acting suspiciously by the basement of his block of flats at 14/16 Novosyolov Street, literally New Settlers Street. Vasiliev said: ‘A white was parked outside the entrance, with the boot towards the entrance. In the car were two men, young men, also young, about 20 or 25 years old.’

Vasiliev noticed that the last two digits of the car number plate had been stuck on with paper, showing 62, the Ryazan regional code. Underneath the paper was the true plate number, giving a Moscow code. Vasiliev, puzzled, decided to call the police. ‘As we were waiting for the lift and it was empty, one of the young guys got out of the car and the girl asked: "have you done everything?" "Yes." "OK, let’s go." And they got into the car and quite quickly left.’

Vasiliev observed the three in the car with the mismatched plates. ‘I remember the driver sat at the wheel, quite thin, with a moustache, and the other man was heavier. The girl had blond hair, cut short, wearing sports clothes and a leather jacket. They were Russian, absolutely, not Asiatic.’

The police arrived. Inspector Andrei Chernyshev from the local police was the first to enter the basement. He said: ‘we had a signal from a man on duty. It was about 10 in the evening. There were some strangers who were seen leaving the basement from the Building 14/16 at Novosyolovo Street. We were met by the girl who stood by the building. She told us about the men who came out from the basement and left with the car with a licence number which was covered with paper. I went down to the basement. This block of flats had a very deep basement which was completely covered with water. We could see sacks of sugar and in them some electronic device, a few wires and a clock. We were shocked. We ran out of the basement and I stayed on watch by the entrance and my officers went to evacuate the people.’

Grandmother Clara Stepanovna recalled that night: ‘the neighbours began to knock at the door and said: "get out fast, something’s been planted underneath us." We quickly grabbed what we could and leapt out. My daughter leaped out not dressed, without stockings, without tights, not anything, just flung a jacket on. The kids also dashed out not dressed. They held us away from the block of flats and started investigating. They didn’t give us permission to come near.’

Vasiliev said: ‘After we were standing in the square, my wife remembered that she hadn’t switched off the stove, so I went up to an MVD officer to tell him. We went up in the lift. He told me they had really had found a device.’ (MVD stands for Ministerstvo Vnutrennykh Del, the Interior Ministry.)

Yuri Tkachenko, head of the local bomb squad, went down into the basement. ‘For me it was a live bomb. I was in a combat situation,’ he said. He tested the three sugar sacks in the basement with his MO-2 portable gas analyser, and got a positive reading for Hexogen, the explosive used in the Moscow bombs.

The timer of the detonator was set for 5.30am, which would have killed many of the 250 tenants of the 13-storey block of flats.

The sacks were taken out of the basement at around 1.30 in the morning and driven away by the FSB. But the secret police left the detonator in the hands of the bomb squad. They photographed it later that day.

As the residents were finally allowed back into to their homes at seven in the morning, one of the policemen let Mrs Stepanovna see what was left. She said: ‘there was a bit left, and the policeman said: "there, that’s it. That’s the stuff that was meant to blow you up.’

The local police arrested two men that night, according to Boris Kagarlitsky, a member of the Russian Institute of Comparative Politics. ‘FSB officers were caught red-handed while planting the bomb. They were arrested by the police and they tried to save themselves by showing FSB identity cards.’

Then, headquarters of the FSB in Moscow intervened. The two men were quietly let go.

The next day, on September 24, the FSB in Moscow announced that there had never been a bomb, only a training exercise. There was no hexogen, only sugar. Pro-Kremlin newspapers reported that the Ryazan bomb squad had made a mistake when they detected hexogen. One newspaper commented that perhaps they hadn’t washed their tester, a remark to which Tkachenko the bomb disposal expert replied: ‘it wasn’t an enema. There are two sources of radiation in the tester. These people don’t know what they are talking about.

Alexander Sergeyev, head of the Ryazan regional FSB, said, when asked about the training exercise: ‘the decision wasn’t taken by our local FSB. If it was a training exercise, it was done for everyone to check the combat readiness of all the towns in Russia. Nobody told us it was a training exercise and we didn’t receive a call that it was over. For two days and nights, we didn’t receive any documents or order that it was finished.’

Officially, the Minister of Interior has forbidden the police and the FSB from talking about the bomb that never was. But few believe the Kremlin’s version that it was only a training exercise.

Vasiliev said: ‘I heard the official version on the radio, when the press secretary of the FSB announced that it was a training exercise. It felt extremely unpleasant. A lot of neighbours started to call me and say: "did you hear that?" I heard it, but I cannot believe it.’

The credibility of the FSB version of events hangs on the notion of a training exercise. Why use real hexogen and a real detonator in a dummy bomb? If was just a training exercise, why turn out the residents of the block of flats for a sleepless night? And why should the Ryazan bomb squad be so concerned about a dummy detonator that they took a photograph of it?

The concern of locals deepened when the newspaper Novaya Gazeta alleged that sacks of hexogen were found at a military base in Ryazan. The paper reported that a paratrooper on guards duty at a weapons warehouse outside the city discovered piles of sacks labelled sugar. He opened one of the bags and tried to use the white powder to sweeten his tea, only to recoil at the taste. An explosives expert called in to examine the bags declared that they contained hexogen.

Putin has declared: ‘there is nobody in the Russian special services capable of committing such a crime against our people. It is immoral even to consider such a possibility. In fact, this is nothing but an element of the information war against Russia.’

His problem is that the residents of the Ryazan block of flats, among others,

do not believe his word or the word of the FSB on the matter.

Copyright 2000 John Sweeney.

No limits on reproduction or distribution. Credit John Sweeney; and Cryptome if you like but not required.